It's been two weeks since my last update, and while I've been working a little at FSK, I've not managed to get as much done as I'd like to have done (German admin and paperwork is legendary for a reason!). Nonetheless, I've made progress with the project, and I've got plenty to write about in this edition of the blog. Some brief updates are as follows:

- Archivematica and its storage module have successfully been installed on our internal servers. After several weeks of fiddling around on the part of our dedicated tech team, we've been able to get Archivematica into a somewhat working state. I still have quite a lot to learn about how to use it to process material, but having a stable, working instance allows me to study it in my own time over the coming weeks and months.

- The first plenum of FSK since I arrived at the organisation happened a couple of weeks ago. Unfortunately I wasn't able to attend, but a colleague presented a brief introduction of the archives project to generally wide support. This is good news! Organisational support is key to the success of an archives project in any organisation, from the most corporate and capitalist to the most decentralised and anarchist.

- Even more archival material has been discovered! A large cabinet of vinyl records, MiniDiscs, cassettes, and some papers from FSK's early days - all very exciting for the archive. However, it's being stored ... in the smoking room. Not the best environment for such fragile material. We're working to move the cupboard into a more sensible storage location so further damage can be limited. When I was told this series of updates, it was like an archival rollercoaster - first happiness and interest in the new material, then despair when I saw the conditions it was stored in, then mild relief when I found out that it was being moved. If we choose the right location for the cupboard, it could even form the basis of a dedicated archive store room! Swings and roundabouts after all.

Now I've brought you up to date, let's dive into the meat of this blog post: how working with open-source archival software like Archivematica and AtoM allows us to widen participation, develop independent, radical histories, and resist the monopolisation of the past by state and corporate archives.

Archivematica, the software we've decided to use for digital preservation and records management, is quite well known in the archives field. It's open source, and since 2007 it's been one of the go-to options for archivists and records managers working in situations with limited resources. As I mentioned in my last blog, it pairs automatically with AtoM (Access to Memory), allowing archivists to create a streamlined workflow from the ingest of digital material right the way through to the creation of a user-friendly, public-facing catalogue. In theory, this sounds like a very smooth process, and by rights it should be - the Archivematica team have created a (nominally) single-install, well-documented package which allows the user to quickly install and set up the software. However, as we found at FSK, this process is easier said than done. The installation package is made up of several much smaller toolkits and addons, a large amount of which are also open-source and maintained by volunteers. If even one of these develops an issue, the whole Archivematica installation won't work properly (as we found out, repeatedly).

After troubleshooting and examining the installation in almost exhaustive detail, the tech team and I finally made a breakthrough. Now we've got a working instance of Archivematica! This whole process, though, does highlight some of the main issues that emerge when working with open-source archival software. Since there's no income stream from subscriptions or licence purchases, the developers are either working voluntarily, or by relying on donations from users. As such, it's rare that the development team can work on the software full-time, thus making it much more likely for issues or inefficiencies to creep in. This isn't to say, of course, that the developers of open-source software are any less skilled or dedicated than their counterparts working on paid software. The nature of the capitalist nightmare in which we live is, unfortunately, one which strongly discourages voluntary not-for-profit projects. As I'll get on to below, the profit motive and its associated paywalls and licence fees go a long way towards stifling projects like the FSK archive before they can get off the ground.

Open-source software does come with a whole host of benefits as well, though, especially for an organisation like FSK. We don't have any kind of a budget for software, let alone for the establishment of an archive. The existence and continued development of tools like AtoM, Archivematica and its equivalents allows much wider participation in archives world by a greater variety of organisation and communities. The existence of a financial barrier to entry prevents the voices of disadvantaged communities and organisations with no access to funding from being heard. This, in turn, allows archives with more substantial financial support to dominate the archival landscape.

I feel like the readership of this blog won't need too much of an explanation as to the dangers of having the world of primary historical sources and organisational accountability being controlled by only the organisations who have significant financial backing - so I'll keep it relatively short. If organisations like the state (through national archives), universities, and private museums are allowed to be the sole arbiters of historical and archival preservation, huge parts of the past risk being buried. For one particularly large-scale example of this, see the UK's 'Operation Legacy' - an unknown (but very large) amount of records from the Colonial Office were destroyed in order to cover up crimes committed by the UK government in its former colonies. The remainder of these are still stored in the UK (a fact which was only made public knowledge in 2011!), against the will of the now independent countries to which they rightfully belong. This collection, stored at the National Archives in Kew, is known by the highly euphemistic name of "The Foreign and Commonwealth Migrated Archives". Here we can see one of the ways in which archives, even by their names, can work to support a state-approved narrative: the use of the term "migrated" obscures the violent, illegal process by which these archives have been forcibly removed from their original setting and concealed by the UK government.

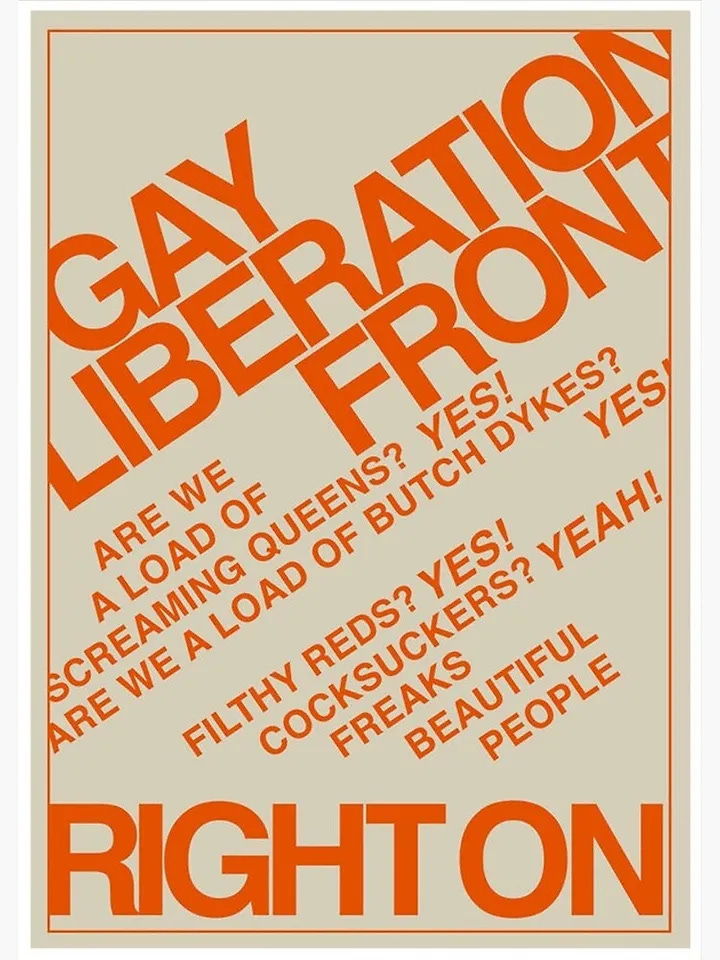

Preventing, or at least combatting, this monopoly on knowledge is a key benefit of reducing the barrier to entry to archives' creation. The existence and accessibility of alternate histories, activist narratives, and documentation of resistance provides a valuable resource for those in the present day seeking to improve the material conditions of their own communities. For activists (for example), such archives provide inspiration, hope, and a basis from which to build their theory and praxis in the modern day. Open-source, community-owned archives are a way in which communities can take control over their own histories, preventing them from being co-opted by the state or dominant societal groups. Think about the way in which the queer rights movement in the UK has been de-radicalised - think about the solidly left-wing, socialist and anarchist organisers who made up a significant part of the push for recognition in the 1970s and 80s. In the 2020s, due to the concerted efforts of subsequent governments and corporations, the mainstream queer rights movement is almost entirely assimilated into capitalist society, significantly weakening its radical change-making potential.

All this to say that while getting to grips with some of the open-source software on the market currently can be a real pain, it's worth it to be able to establish independent radical archives which are able to exist outside the profit-driven system which has consumed so much of the GLAM sector. I've written extensively about bias in archives, as well as the benefits of personal and community archiving practices - open source software is, in my view, key to ensuring these practices can continue. My work at FSK aims to do just this, by ensuring that the radio station's past broadcasts aren't lost to bit rot, degradation of magnetic tape, or simply by being lost within the building's many offices. By keeping all the cataloguing, storage and management in-house, we as a collective are able to decide what we want and need from the archive, allowing us to create policies, processes, and standards in keeping with FSK's own principles.